microscopic examination of urine pdf

- by cooper

Microscopic urine examination is a crucial diagnostic tool, analyzing liquid waste for abnormalities. It reveals insights into kidney function and overall health, aiding in disease detection.

Urinalysis, including microscopic assessment, plays a vital role in diagnosing urinary tract infections, kidney diseases, and metabolic disorders, guiding effective treatment strategies.

What is Microscopic Urine Examination?

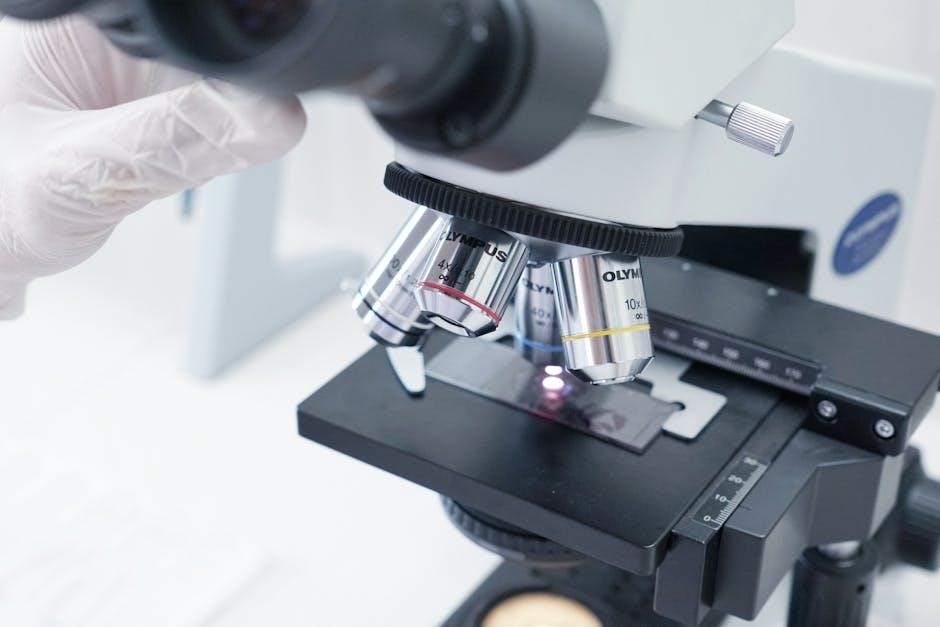

Microscopic urine examination is a laboratory procedure involving the analysis of urine sediment under a microscope. This process allows healthcare professionals to identify and quantify various cellular components and other elements present within the urine. It goes beyond the basic chemical dipstick test, providing a detailed assessment of the urinary tract’s health.

The examination begins with centrifuging a urine sample to concentrate any solid particles, forming a sediment. This sediment is then placed on a microscope slide and carefully examined. Key elements assessed include red blood cells, white blood cells, epithelial cells, casts, crystals, and microorganisms like bacteria. Identifying these components helps pinpoint potential issues within the kidneys, bladder, and associated structures. The process is fundamental in diagnosing infections, kidney diseases, and metabolic disorders, offering crucial insights into a patient’s condition.

The Role of Urinalysis in Diagnosis

Urinalysis, encompassing both macroscopic and microscopic examination, is a cornerstone of diagnostic medicine. It serves as a non-invasive initial assessment for a wide range of conditions, from urinary tract infections (UTIs) to systemic diseases like diabetes and kidney failure. The microscopic component specifically aids in identifying the cause of observed abnormalities detected in the initial dipstick test.

For instance, the presence of white blood cells and bacteria suggests a UTI, while red blood cells may indicate kidney damage or stones; Analyzing casts can pinpoint specific kidney diseases, and identifying crystals can reveal metabolic disorders. Urinalysis isn’t typically a standalone diagnostic tool; rather, it provides crucial clues that guide further, more specific testing. It helps clinicians narrow down possibilities, leading to faster and more accurate diagnoses, ultimately improving patient care and treatment outcomes.

Components of Normal Urine

Normal urine is primarily water, with dissolved wastes like urea, creatinine, and electrolytes. A healthy sample contains minimal cells, casts, or crystals, reflecting kidney efficiency.

Normal Urine Composition

Normal urine is a complex aqueous solution, approximately 95% water, reflecting the body’s hydration status and metabolic processes. The remaining 5% comprises a diverse array of dissolved substances, including both organic and inorganic compounds. Significant organic components include urea, a primary nitrogenous waste product resulting from protein metabolism, and creatinine, generated from muscle metabolism.

Uric acid, another metabolic byproduct, is present in varying amounts, influenced by diet and genetic factors. Electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, chloride, and phosphate are crucial for maintaining fluid balance and nerve function, and are actively filtered and reabsorbed by the kidneys. Small amounts of amino acids, vitamins, and hormones are also typically found.

Microscopically, normal urine should exhibit a minimal number of epithelial cells, a few hyaline casts, and no evidence of bacteria, significant cellular elements, or abnormal crystals. The precise composition fluctuates based on dietary intake, physical activity, and overall health, but deviations from this baseline can signal underlying medical conditions.

Formation of Urine: A Brief Overview

Urine formation is a multi-stage process primarily occurring within the kidneys, essential for maintaining homeostasis. It begins with glomerular filtration, where blood is filtered through the glomeruli, creating a fluid called filtrate. This filtrate contains water, electrolytes, and small molecules, but importantly, also waste products like urea and creatinine.

Next, tubular reabsorption selectively returns essential substances – glucose, amino acids, and a significant portion of water and electrolytes – back into the bloodstream. Simultaneously, tubular secretion actively transports additional waste products and toxins from the blood into the tubules.

Finally, the remaining fluid, now concentrated urine, flows through the ureters to the bladder for storage, and ultimately expelled via the urethra. This intricate process ensures the removal of metabolic wastes while conserving vital nutrients and maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, a process crucial for overall health and detectable through microscopic examination.

Microscopic Examination: Key Elements

Microscopic analysis identifies cells, casts, and crystals within urine, providing crucial diagnostic clues about kidney health and potential underlying medical conditions.

Erythrocytes (Red Blood Cells) in Urine

The presence of erythrocytes, commonly known as red blood cells (RBCs), in urine – a condition termed hematuria – is not typically normal and warrants investigation. While a few RBCs can be present due to vigorous exercise or menstruation, consistently elevated levels signal potential issues.

Microscopic examination distinguishes between occasional RBCs and significant amounts, often quantified as RBCs per high-power field (RBCs/HPF). Causes of hematuria range from urinary tract infections (UTIs) and kidney stones to more serious conditions like glomerulonephritis, tumors, or trauma.

RBC morphology can also provide clues; for example, crenated (shrunken) RBCs suggest concentrated urine, while dysmorphic RBCs (irregularly shaped) often indicate glomerular origin. Accurate identification and quantification of RBCs are essential for proper diagnosis and management.

Leukocytes (White Blood Cells) in Urine

The detection of leukocytes, or white blood cells (WBCs), in urine – a condition known as pyuria – is a strong indicator of inflammation within the urinary tract. While a small number of WBCs can be normal, consistently elevated counts typically suggest an infection or inflammatory process.

Microscopic examination quantifies WBCs per high-power field (WBCs/HPF), helping to assess the severity of inflammation. Common causes of pyuria include urinary tract infections (UTIs), particularly cystitis and pyelonephritis, but can also stem from kidney diseases or interstitial nephritis.

The presence of WBC casts – formed when WBCs clump together within the kidney tubules – is a particularly significant finding, often indicating kidney inflammation. Distinguishing between different types of WBCs (neutrophils, lymphocytes) can further refine the diagnosis.

Epithelial Cells in Urine

Epithelial cells are normally present in small numbers in urine, originating from the shedding of cells lining the urinary tract. Their identification and quantification during microscopic examination can provide clues about the source and extent of urinary tract involvement.

Several types of epithelial cells can be observed, including squamous, transitional, and renal tubular epithelial cells. Squamous cells, originating from the lower urethra and vagina, are commonly found and generally considered non-pathogenic unless present in large numbers.

Transitional epithelial cells, derived from the bladder and ureters, are more significant findings, potentially indicating inflammation or malignancy. Renal tubular epithelial cells, originating from the kidney tubules, are less common and their presence often suggests kidney damage or disease.

Squamous Epithelial Cells

Squamous epithelial cells are the largest cells typically observed in urine sediment, originating from the lining of the urethra and the lower portion of the urinary tract, and even external contamination. They appear flat and irregular with a prominent nucleus, often exhibiting a polygonal shape.

Their presence in small numbers is considered normal, particularly in routine urine samples, as they are easily shed from the urethra. However, a significant increase in squamous cells can indicate contamination of the sample during collection, requiring a repeat test.

Clinically, abundant squamous cells generally don’t signify a primary urinary tract pathology. However, their presence should prompt careful consideration of the collection technique to ensure accurate diagnostic interpretation and avoid misleading results. They are rarely indicative of kidney disease.

Transitional Epithelial Cells

Transitional epithelial cells line the urinary tract from the renal pelvis to the upper urethra and bladder. These cells are larger than squamous cells, exhibiting a rounded or pear-shaped appearance with a centrally located nucleus, often appearing binucleated. Their cytoplasm can be slightly basophilic.

Finding a few transitional cells in urine is generally considered normal, representing natural shedding from the urinary tract lining. However, an increased number can suggest inflammation, infection, or even malignancy within the urinary system.

Notably, the presence of atypical transitional cells – those with enlarged nuclei or irregular shapes – warrants further investigation, potentially indicating bladder cancer or other serious conditions. Careful microscopic evaluation and correlation with clinical findings are crucial for accurate diagnosis.

Casts in Urine

Urine casts are microscopic cylindrical structures formed within the distal convoluted tubules and collecting ducts of the kidneys. They represent a mold of the tubule lumen created by Tamm-Horsfall protein, secreted by tubular epithelial cells. Various elements can become trapped within this protein matrix, leading to different types of casts.

Their identification is clinically significant, as the type of cast present can indicate specific kidney diseases or conditions. For instance, hyaline casts are common and often benign, while cellular casts suggest inflammation or damage to the kidney tubules.

Analyzing casts helps differentiate between glomerular and tubular diseases, aiding in accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment planning. The presence, number, and type of casts are all important considerations during microscopic urine examination.

Hyaline Casts

Hyaline casts are the most frequently observed type of urinary cast, appearing as clear, colorless cylinders under the microscope. They are primarily composed of Tamm-Horsfall protein, a mucoprotein secreted by the tubular epithelial cells of the kidneys. Their formation is often associated with decreased urine flow, concentrated urine, or strenuous exercise.

Generally, a few hyaline casts are considered normal, particularly in individuals who are dehydrated or have undergone vigorous physical activity. However, a large number of hyaline casts may indicate underlying kidney disease, though they are not specific to any particular condition.

Clinical significance lies in their presence as a potential indicator of altered kidney function, prompting further investigation to rule out more serious pathology. They serve as a baseline finding when assessing for other, more indicative cast types.

Cellular Casts

Cellular casts are significant findings in microscopic urine examination, indicating active kidney disease or inflammation. These casts form when cells adhere to the Tamm-Horsfall protein matrix within the renal tubules, creating a cylindrical mold of cellular material. Their identification is crucial for accurate diagnosis.

Several types exist, including red blood cell casts (indicating glomerulonephritis or vasculitis), white blood cell casts (suggesting pyelonephritis or interstitial nephritis), and epithelial cell casts (often seen in acute tubular necrosis or severe kidney damage).

The presence of cellular casts is generally considered pathological and warrants further investigation to determine the underlying cause. The specific type of cell within the cast provides valuable clues regarding the location and nature of the kidney injury, guiding appropriate treatment strategies and monitoring disease progression.

Crystals in Urine

Crystals in urine are common findings during microscopic examination, often influenced by urine pH, concentration, and temperature. While many are benign, their presence can indicate underlying metabolic disorders or kidney stone formation risk. Identifying crystal types is therefore clinically significant.

Common crystals include uric acid crystals (associated with gout or high purine intake), calcium oxalate crystals (the most frequent type, linked to kidney stones), and triple phosphate crystals (often seen in urinary tract infections).

Crystal formation is affected by hydration status; concentrated urine promotes crystallization. Certain medications and dietary factors can also contribute. While not always pathological, abundant or unusual crystals necessitate further investigation to rule out metabolic abnormalities or kidney disease, guiding preventative measures and treatment.

Bacteria and Other Microorganisms

Microscopic examination can reveal the presence of bacteria and other microorganisms in urine, strongly suggesting a urinary tract infection (UTI). Identifying bacteria type isn’t typically done directly via microscopy, but their presence warrants further investigation via urine culture for definitive identification and antibiotic sensitivity testing.

Significant bacteriuria, a high number of bacteria, usually indicates infection. However, contamination from vaginal flora is common, especially in female samples, requiring careful interpretation. Beyond bacteria, other microorganisms like yeast (Candida species) can also be observed, indicating fungal infections.

Parasites, though less common, may occasionally be detected in urine, particularly in individuals with specific travel histories or compromised immune systems. The presence of any microorganism necessitates correlation with clinical symptoms and further laboratory testing for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Interpreting Microscopic Findings

Microscopic urine analysis requires careful correlation with patient symptoms and other lab results for accurate diagnosis. Findings alone aren’t definitive; context is key.

Correlation with Clinical Symptoms

Interpreting microscopic urine findings demands a holistic approach, meticulously correlating laboratory observations with the patient’s presenting clinical symptoms. Isolated findings, such as the presence of a few white blood cells, may be insignificant in an asymptomatic individual but highly suggestive of a urinary tract infection when accompanied by dysuria, frequency, and urgency.

Similarly, the detection of red blood cells requires careful consideration. While benign causes like strenuous exercise or menstruation can induce hematuria, it could also signal more serious conditions like kidney stones, glomerulonephritis, or even bladder cancer, necessitating further investigation based on associated symptoms like flank pain or visible hematuria.

Furthermore, the type and quantity of casts observed must be interpreted in the context of the patient’s overall clinical picture. Hyaline casts are often considered normal, but their abundance, or the presence of cellular casts, can indicate specific kidney diseases. A comprehensive assessment, integrating microscopic findings with clinical presentation and other diagnostic tests, is paramount for accurate diagnosis and effective patient management.

Limitations of Microscopic Examination

Microscopic urine examination, while valuable, possesses inherent limitations that clinicians must acknowledge. The sensitivity of the test is affected by sample collection techniques, storage duration, and the skill of the microscopist; delayed reading can lead to cellular disintegration and inaccurate counts.

Furthermore, certain conditions may yield false negatives. Low-grade infections or early-stage kidney disease might not produce sufficient abnormalities detectable under the microscope. Conversely, contamination from vaginal secretions or menstrual blood can cause false positives, particularly regarding red blood cell counts.

It’s crucial to remember that microscopic analysis provides a snapshot in time and doesn’t always reflect the dynamic nature of kidney disease. Therefore, it should never be interpreted in isolation but rather integrated with other diagnostic modalities like urine culture, serum creatinine levels, and imaging studies for a comprehensive assessment.

Related posts:

Need a handy urine microscopy reference? Download a clear, concise PDF guide now! Perfect for students & healthcare pros. Get your free copy!

Posted in PDF